Everything In Moderation

Hey all. Let’s hop to it.

Politics

I’ve been working for the past month on a review of some books about the history of the Democratic Party. I’m not really sure it’ll end up the way I’d planned it or if it’ll wind up running at all, really, but it’s been a good exercise, and I’ve learned a lot from the texts I’ve consulted. One of them is The New Democrats and the Return to Power — a 2013 book by Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) founder Al From on the triumph of Democratic centrists in the 1980s and 1990s and the party’s bright future, as confirmed by Obama’s then-recent reelection. “In 1985, out of the political rubble arose the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), the birthplace of the New Democrat political movement,” he writes in the introduction. “Less than eight years later Bill Clinton won the presidency, having prepared for his White House run by chairing the DLC. Today’s Republicans will have to find their own formula. But they would be wise to start by rebuilding their party intellectually.” He offers more concrete advice for Republicans in the book’s closing chapter:

The Republicans will nominate a candidate in 2016. But the chances of any Republican winning—barring a national catastrophe—will be severely diminished if they don’t change their party. So, I’d suggest that they declare a moratorium on candidate talk during 2014—and encourage all the potential candidates to work together to forge a new, forward-looking, inclusive agenda that appeals to voters they’ve been losing or turning away and that a candidate can take into the general election. Then in 2015, the candidates can fight over whom can best carry their new agenda to the American people.

Second, that new agenda has to be more inclusive. Mitt Romney’s message of self-deportation for undocumented immigrants did not offer a welcome mat to Hispanics, the fastest growing constituency in the changing electorate. In our case, with a much different electorate, we couldn’t win without increasing our appeal to what Clinton called the “forgotten middle class” who had been leaving our party in droves. In today’s electorate, I believe it will be hard for the Republicans to win without a vastly more appealing message to Hispanics. The Republicans have a harder road to hoe than we did. Because we were already a diverse party, bringing back middle-class voters did not fundamentally change our coalition. After all, they had been part of it before they left. But the Republicans are a homogenous, nearly all-white party. Bringing in Hispanics will require a big change in their coalition.

Third, they need to become more tolerant on cultural issues. The Republicans will likely always be the more conservative party on cultural issues, and that doesn’t have to change. But they can’t allow intolerant, extremists on the cultural right to dominate their party. If they do, the voters they need won’t even listen to them about the issues they might agree on.

Republicans ought to look carefully at how Clinton talked about the abortion issue in 1992. He said abortions should be legal, safe, and rare. By saying abortions should be legal and safe, he was reassuring his pro-choice supporters. Because Clinton was clearly pro-choice, he was never going to win votes from the most extreme pro-life voters. But most voters are not on the extremes of the abortion issue—whether pro-choice or pro-life.

In 1992, a substantial part of the electorate was what I characterize as soft pro-life. They were against abortion most of the time but not in every instance. By saying abortion should be rare, Clinton was telling those voters that while he disagreed with them, he understood why someone may have concerns about abortion. As a result, many of those soft pro-life voters were open to examining Clinton’s positions on other issues, and when they did, many of them voted for him.

In the years before 1992, columnist Michael Barone used to call the Democrats the “stupid” party. If the Republicans don’t change—and fast—they’ll earn that appellation.

I’ve written previously about how and why predictions of the GOP’s electoral collapse were wrong, so I won’t repeat myself at length here. It is worth asking, though: which party looks like the stupid party today?

Really, we know From himself would say the Democrats have reclaimed the title, albeit for different reasons than I would. He and other moderate operatives were just featured in a piece by Jason Zengerle in the New York Times Magazine about “the vanishing moderate Democrat.” There isn’t a thought in it you haven’t heard before — Democrats have moved left, moderates are marginalized and vulnerable, and if the party doesn’t get its act together, it’s going to keep losing the moderate-to-conservative voters it needs to stay competitive in Washington. What I find most interesting about From’s book, though, is that it captures the mood of party moderates before the current political landscape took shape. Obama and party leaders since Clinton, per From, had done most things right, and there still wasn’t much of a left to even complain about. If moderates are correct about everything that fundamentally ails the party, Democrats, and Democratic moderates in particular, ought to have been in tip top shape back then. In fact, From suggests they were on the cusp of a generational victory.

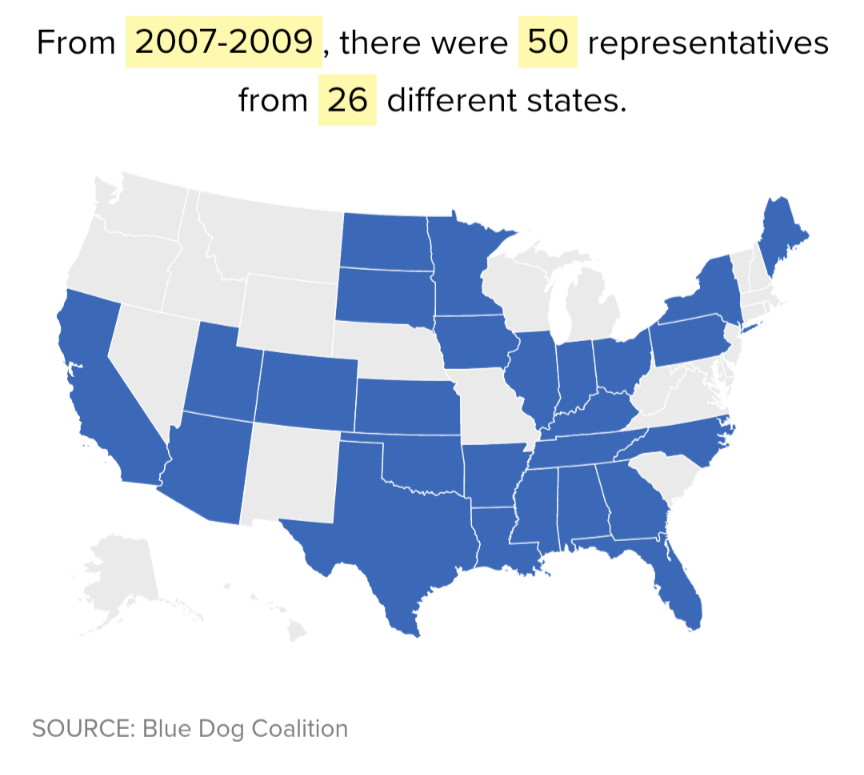

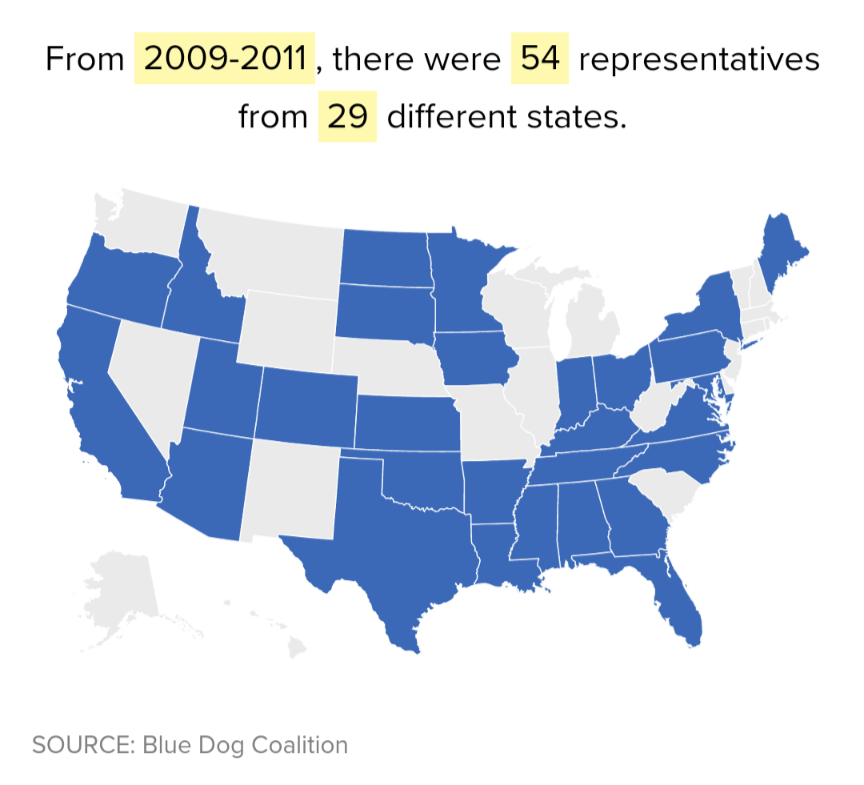

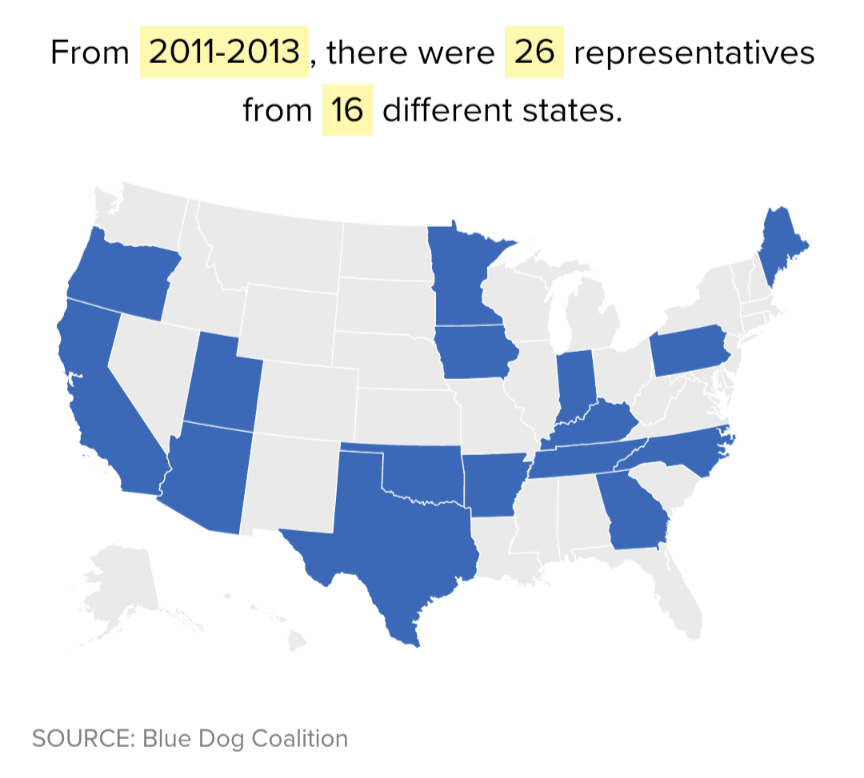

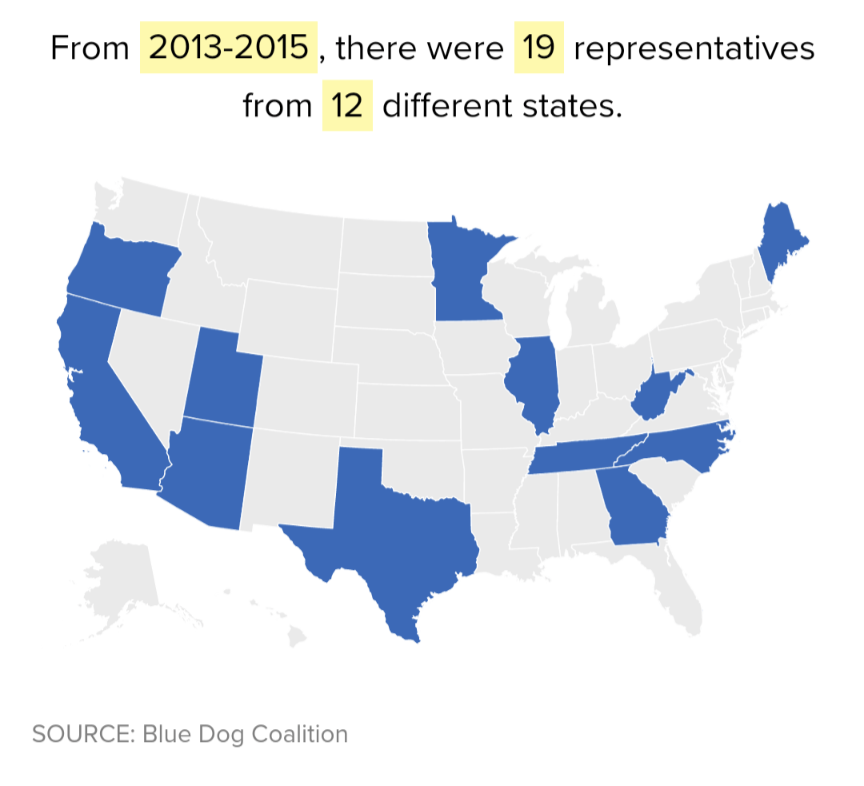

But they weren’t, actually. Here are some maps Politico featured in an actually fairly optimistic 2017 piece on the past and future of moderate-to-conservative Blue Dog Democrats.

As you can see and may well remember yourself, moderate Democrats were absolutely walloped in the 2010 midterms — and walloped for reasons that, as I’ve said before, did not include tweets about defunding the police. Their numbers have never recovered. And even if you happen to believe that progressive rhetoric poses a challenge for Democrats in swing districts, the reality remains that the national Democratic Party’s fortunes in Washington were shifting while non-progressives had full run of the place during Obama’s first term.

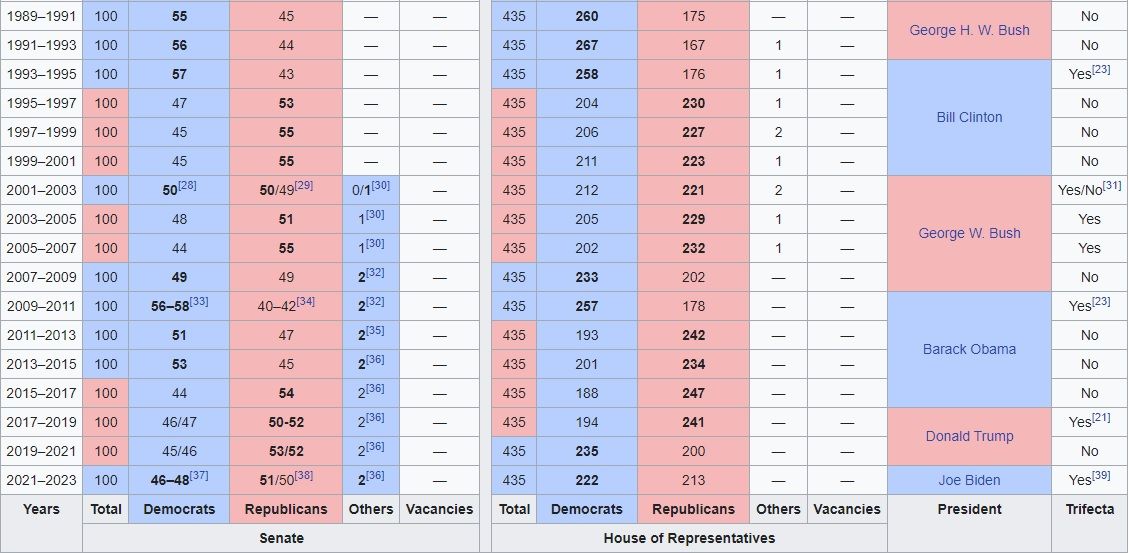

And really, the electoral rot began well before that. Here are the last 30 or so years of power in Washington.

And here, by the way, is Congressman Josh Gottheimer’s take on the Clinton years from Zengerle’s piece:

He pressed play and his iPhone screen filled with waving American flags as an old but familiar voice emerged, proclaiming, “I am honored to have been given the opportunity to stand up for the values and the interests of ordinary Americans.” The video was a television advertisement from Bill Clinton’s 1996 re-election campaign. Over images of construction workers and children and police officers, a series of bold captions touted Clinton’s first-term accomplishments: “WELFARE REFORM, WORK REQUIREMENTS”; “TAXES CUT FOR 15,000,000 FAMILIES”; “DEATH PENALTY FOR DRUG KINGPINS.” His promises for a second term followed: “BAN ‘COP-KILLER’ BULLETS”; “CAPITAL GAINS TAX CUT FOR HOME OWNERS”; “BALANCE THE BUDGET FOR A GROWING ECONOMY” “We are safer, we are more secure, we are more prosperous,” Clinton said. When the ad was over, Gottheimer says, he looked at Pelosi. “This is how we won,” he told her, “and this is how we win again.”

Clinton did, of course, go on to win that reelection campaign — a race that, like his victory in 1992, has been touted in defense of the party’s approach to politics in that era. But that reelection campaign also happened to follow one of the most catastrophic midterm elections in the party’s history, which handed Republicans full control of Congress for the first time in decades. Though no one seems terribly interested in 1994 anymore, the explanations for why Democrats lost so badly were just about the same as the arguments being made about the state of the party now. Clinton, it was said — Bill Clinton! — had veered too far to the left in efforts to appease party progressives.

Over the course of his book, From talks at length about everything he saw going wrong with Clinton’s first term. “With diversity, gays in the military, HIV-positive immigrants, federal funding for abortion, ties with Hollywood and the eastern liberal establishment, I believed he’d put himself too far left on the cultural divide,” he wrote. But he argued in a 1993 memo to Clinton that one particular policy push offered the White House a legacy-defining opportunity to get back on track:

Of all the opportunities you have this fall, NAFTA presents the greatest. Passing NAFTA can make your presidency. NAFTA presents both an economic and political opportunity. Getting the economy off the ground is still the most critical challenge you face, and NAFTA is the most important policy—and maybe the only one—you can pursue this fall to do that. A victory of NAFTA will both create real jobs and demonstrate that you have the vision to lead our country into the world economy at a defining historic moment. It would make it clear that you speak for the national interest, while NAFTA’s adversaries, including Perot, are playing special interest politics as usual. Politically, a victory on NAFTA would assert your leadership over your own party by making it clear that you, not the Democratic leadership in Congress or the interest groups, set the Democratic Party’s agenda on matters of real national importance. And, it would establish the kind of bipartisan coalition on a major issue that you’ll need down the road on health care and welfare reform. I can’t tell you how much better it would make your life and how much it would strengthen your presidency for you to beat [Congressman David] Bonior and organized labor on NAFTA. That would reestablish presidential leadership in the Democratic Party, something that hasn’t happened since 1966.

Remarkably, the memo ended with a thinly-veiled threat that evinces the DLC’s frustration with Clinton at the time:

The bottom line is this. A number of us involved in the DLC have devoted a good portion of our lives to promoting the kind of change in our party and in the country that allowed you to be elected president. You were a partner in the effort. We believe we played a pretty significant role in your election. And we want more than anything else for your presidency to succeed. But we believe it will not succeed if the same forces in Congress and the interest groups that have run the Democratic Party into the ground for the past 25 years continue to dominate the party. We’re prepared to fight preferably with you—but without you, if necessary—to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Clinton obliged, redoubling his efforts to pass not only NAFTA but a crime bill you might have heard a thing or two about over the last few years. Nevertheless, the Democrats got destroyed, a defeat From attributes to the fight over healthcare reform and Clinton’s failure to push through welfare reform in time for the election as well. But the DLC ultimately got most of what it wanted by the end of Clinton’s second term. From, Gottheimer, and the rest would have us believe that those policy victories and the party’s messaging were politically transformative. They might have been, but not for Democrats. Republicans controlled both houses of Congress for all but two years between 1995 and 2007. Democrats lost presidential elections in 2000 and 2004. In 2006, the Iraq War and the unpopularity of the Bush administration did sweep Democrats back into a Congressional majority. In 2008, a candidate who defeated the Clintons in a hard-fought primary rode that dissatisfaction, deepened by a financial crisis, into the White House. In 2012, he won reelection, as most incumbents do, against a replacement level Republican candidate — by less than 4 points after a campaign that had been neck and neck in its final weeks. All told, “how we won,” per Gottheimer, produced, at best, two presidential victories under Clinton alongside an utter collapse in Congress. The same would happen under Obama, whose early-presidency sensibilities the popularists are now urging the party to revisit. No one’s terribly interested in figuring out why.

The moderates do have their own suspicions though, and they have less to do with activists and social issues than the arguments they choose to make in public. Again, the 1994 midterms were preceded by a healthcare fight. So too was the party’s shellacking in 2010. And, clearly, a lot of moderates now see actually pushing for major policy changes as a strategic mistake. It’s true that there are often real political risks to the Democratic Party doing things. From there, a bloc of Democrats have concluded that the Democratic Party should not, in fact, do much of anything. The failure of party moderates, as Jonathan Chait writes in his take on Zengerle’s piece, “to formulate a coherent economic agenda that improves either substantively or politically upon the ideas identified with the party,” is a feature, not a bug. Here, for instance, is Blue Dog Stephanie Murphy’s take on the DCCC’s efforts to whip votes for BBB:

Last summer, during the height of the impasse over the infrastructure bill and Build Back Better, Maloney or members of his D.C.C.C. staff reached out to several centrist representatives to warn that the Democrats’ majority would be in jeopardy if they thwarted Biden’s legislative priorities. Some of these centrists, who face tough re-election campaigns, interpreted the outreach as a not-so-veiled threat that their own fund-raising help from the party would be at risk if they didn’t get in line. “You want your political arm to be focused on politics, not policy,” Murphy told me. “My belief is that the D.C.C.C. has one job and one job alone: to protect incumbents and expand the majority. And becoming an extension of leadership, and working against members that you’re supposed to protect, runs crosswise with your sole mission.”

It’s an old saw now that Democrats can’t really govern. But it should also be understood that a number of party moderates believe the party shouldn’t really govern. I’ve said before that the party’s best understood as a kind of professional association more dedicated to protecting its members than it is to utilizing them to achieve a concrete set of policy goals. Murphy’s statement is one of the clearest bits of evidence for that — beyond the slogans, a few modest proposals like lowering the price of prescription drugs, and a growing reliance on the executive branch for certain administrative reforms, there’s no real there there. Republicans have an actual policy project that comes from a shared ideology and theory of government. They’ve built a set of strong institutions and organizations to advance it even outside of contesting elections. The Democrats haven’t really, partially because they’ve come to believe policy projects are politically dangerous. The other part of it, of course, is that party moderates just don’t agree substantively with progressives that we ought to fundamentally change how our political system and economy work.

Here’s Zengerle on Pennsylvania Congresswoman Susan Wild:

“I’m the biggest cheerleader there is for the industries in our district,” she said, “including industries that sometimes come under attack from some quarters for reasons that aren’t necessarily legitimate.” She noted her support for local cement companies — which environmentalists criticize for their carbon emissions — as well as for an Allentown manufacturer that’s being sued by 35 people who accuse it of emitting a toxic gas that caused their cancers. “The fact of the matter is, the legal process will probably take care of it before any kind of regulatory process will,” she said of the case. “But the main thing, again, for me, is being willing to be pro-business.”

Wild is not unusual among moderate Democrats in promoting an economic agenda that champions the interests of industry, Wall Street and the affluent. Although Josh Gottheimer spends a lot of time jousting with the Squad, his signature issue is raising or eliminating the cap on the state and local tax deduction — not exactly a pressing concern of working-class voters. (Relatedly, Gottheimer doesn’t need to worry about appealing to small-dollar donors. A favorite of Wall Street donors, he currently has $13 million in his campaign war chest.)

I think it’s important that Gottheimer, Murphy, and Wild aren't all that old and aren't in leadership. In fact, they position themselves nearly as much against party leaders as they do against progressives and the Squad. This is one of the reasons why I think it’s a mistake to see a generational shift as the real fix the party needs, though, as Perry Bacon Jr. wrote in a recent column, the party’s leaders really have been in power for a remarkably long time:

It’s worth emphasizing just how long many Democratic leaders have been at the helm. In 2003, Pelosi became leader of the House Democrats, Steny H. Hoyer (D-Md.) became the party’s No. 2, and Clyburn became, the third-ranking leader. Biden, then a senator, was the top Democrat on the Foreign Relations Committee. Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (N.Y.) and Majority Whip Richard J. Durbin (Ill.) have been in the party’s Senate leadership since 2005. The Republicans who held equivalent roles when these Democrats took power were Rep. J. Dennis Hastert (Ill.), Rep. Tom DeLay (Tex.), Rep. Deborah Pryce (Ohio), Sen. Richard G. Lugar (Ind.), Sen. Mitch McConnell (Ky.) and Sen. Elizabeth Dole (N.C.). All the Republicans but McConnell are long gone from national politics.

But here’s his list of figures who might change the party for the better if they take the helm:

There is a real ideological divide between the center-left and left in the Democratic Party. But I think an equally and perhaps more important fissure is between the political approach of the Old Guard and those who embrace a modern style of politics, such as Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear, California Gov. Gavin Newsom and Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker; Sens. Brian Schatz (Hawaii) and Elizabeth Warren (Mass.); Reps. Jamie B. Raskin (Md.), Adam B. Schiff (Calif.), Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley (Mass.); Boston Mayor Michelle Wu; Florida Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried; and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg.

Really, there’s not much that unites these people beyond maybe a facility for social media. Buttigieg is perhaps the most instructive choice here – while he came out of the gate in the 2020 primaries with some progressive rhetoric and a real emphasis on the need for structural reforms, he dialed all of that back in a move for the party’s center, as I wrote in my profile for The New Republic. Inevitably, that’s where the strivers end up given the very structural challenges Buttigieg raised and the influence of capital. It just isn’t obvious to me that progressives are set to naturally inherit the party from moderates as the ones at the top age out. I still doubt there’s going to be any real substitute for building organizations and an actual constituency for left politics outside the party. Not much of what we need is going to come from within it. The moderates have seen to that.

Reasons to Be Cheerful

Stranger Things has been very, very good for Kate Bush, who owns her own copyrights. From CBS:

Singer Kate Bush has garnered legions of new fans thanks to Netflix's "Stranger Things" tapping her 1985 hit "Running Up That Hill" as a talismanic song for the character Max Mayfield.

It's also brought her a financial windfall, delivering about $2.3 million in streaming royalties in the month since the show's latest season was released, according to Luminate, which was formerly known as Nielsen Soundscan. Because she owns the copyright to her recordings, she's likely keeping the bulk of that money, according to music industry publication Music Business Worldwide.

Bush noted in a June 17 blog post that the resurgence of the haunting song had put it "on top of that hill" and that its swift climb felt "driven along by a kind of elemental force." It's an unusual twist in the career of a musician who garnered critical acclaim but who hadn't scored a top 10 hit in the U.S. — until this year, 37 years after "Running Up That Hill" was first released.

“Running Up That Hill” is now the most streamed song in the world. Per CNN, Bush “now holds the records for longest time for a track to reach No.1 on the UK's official singles chart; oldest female artist to reach No.1 on the UK's official singles chart; and longest gap between No.1 spots on the UK's official singles chart.”

A Song

"Wow" - Kate Bush (1978)

More to come soon. Bye.

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.