“The Angry U.S. Negro's Rallying Cries Are Confusing His Just And Urgent Cause”

Hey all. Let’s hop to it.

Politics

The New York Times’ Jamelle Bouie gave the newsletter a shoutout (Welcome, new subscribers!) in a recent column on the Democrats’ interminable messaging debate, the subject of another recent column by the Times’ Thomas Edsall. “It’s the same song, each time,” he writes of party moderates. “If progressives would just stop alienating the public, then they could make gains and put power back in Democratic hands. Somehow, the people in the passenger’s seat of the Democratic Party are always and forever responsible for the driver’s failure to reach their shared destination.”

Writing for his newsletter, the journalist Osita Nwanevu made a version of this point earlier in the year. Progressive politicians and activists may be occasionally off-message but in the main, “The simple truth is that most of the things moderate liberals tend to argue Democrats should be doing and saying are, in fact, being done and said by the Biden administration, Democratic leaders in Congress, and the vast majority of Democratic elected officials.”

If, despite their influence, moderate Democrats are not satisfied with the state of their party, then they might want to turn their critical eye on themselves. What they’ll find are a few fundamental problems that may help explain the party’s current predicament.

After all, 2020 was not the first year that Democrats fell short of their expectations. They did so in 2010, when moderates had an even stronger grip on the party, as well as in 2014 and 2016. Here, again, I’ll echo Nwanevu. Despite pitching his administration to the moderate middle — despite his vocal critiques of “identity politics,” his enthusiastic patriotism and his embrace of the most popular Democratic policies on offer — Barack Obama could not arrest the Democratic Party’s slide with blue-collar voters. For the past decade, in other words, “the Democratic Party’s electoral prospects have been in decline for reasons unattributable to progressive figures and ideas that arrived on the political scene practically yesterday.”

One reason for the party’s electoral decline Bouie focuses on is the neoliberal turn in Democratic policymaking. “What was its response to the near-total collapse of private-sector unions?” he asks. “What was its response to the declining fortunes of American workers and the upward redistribution of American wealth? The answer, for most of the past 30 years, is that the moderate Democrats who led the party have either acquiesced in these trends or, as in the case of the Clinton administration, actively pushed them along. And to the extent that these Democrats offered policies targeted to working Americans, they very often failed to deliver on their promises.”

It’s an argument that’s been made often since 2016, and while I think it’s true that the economic collapse of certain white working class communities has helped the right in certain ways, I think it’s important to remember that those voters helped pull Democrats to the center on economics in the first place. White working class Democrats, including union members, broke off from the Democratic Party in huge numbers to back Ronald Reagan; in the Democratic primaries of the 1980s, traditional liberals and progressive candidates lost ground among them to neoliberal Democrats like Gary Hart, Michael Dukakis, and Bill Clinton, who would go on to win pluralities of the white working class vote, according to Alan Abramowitz and Ruy Teixeira, in 1992 and 1996. Clinton remains the last Democrat to have done so.

Now, is this because workers in Scranton and Youngstown took an enthusiastic interest in DLC white papers and tax credit design? Obviously not. But I think the broad messaging of the New Democrats when they emerged — government really has gotten too big; it really does do too much — appealed to, and was in fact crafted to appeal to, white working class voters who had come to believe the government was giving Americans socioculturally distant from them, especially minorities, more attention and resources than they were due.

Again, the failures of neoliberal policies, as they’ve become clear, have probably deepened working class distrust of the Democratic Party and the political system more broadly. That’s not to say that distrust has created a stable base of support for more left-wing policy — as I’ve written previously, turning notional agreement with the left’s ideas into actual power is going to take a lot of work. As for the Democratic Party as a whole, we should bear in mind that its declining support among the white working class doesn’t actually mean it’s lost ground, as is casually said now, with “ordinary Americans.” I can’t do better making this point than Harvard’s Steven Levitsky did in Edsall’s column. “[Democrats] have won the popular vote in 7 out of 8 presidential elections — that’s almost unthinkable,” he said. “They have also won the popular vote in the Senate in every six-year cycle since 2000. You cannot look at a party in a democracy that has won the popular vote almost without fail for two decades and say, gee, that party really has to get it together and address its ‘liabilities.’”

But that’s the discourse we’ve gotten anyway. Much of Edsall’s column is dedicated to airing more criticisms of progressive language and sloganeering from academics like Theda Skocpol.

“The advocacy groups and big funders and foundations around the Democratic Party — in an era of declining unions and mass membership groups — are pushing moralistic identity-based causes or specific policies that do not have majority appeal, understanding, or support, and using often weird insider language (like “Latinx”) or dumb slogans (“Defund the police”) to do it.”

The leaders of these groups, Skocpol stressed, “often claim to speak for Blacks, Hispanics, women etc. without actually speaking to or listening to the real-world concerns of the less privileged people in these categories. That is arrogant and politically stupid. It happens in part because of the over-concentration of college graduate Democrats in isolated sectors of major metro areas, in worlds apart from most other Americans.”

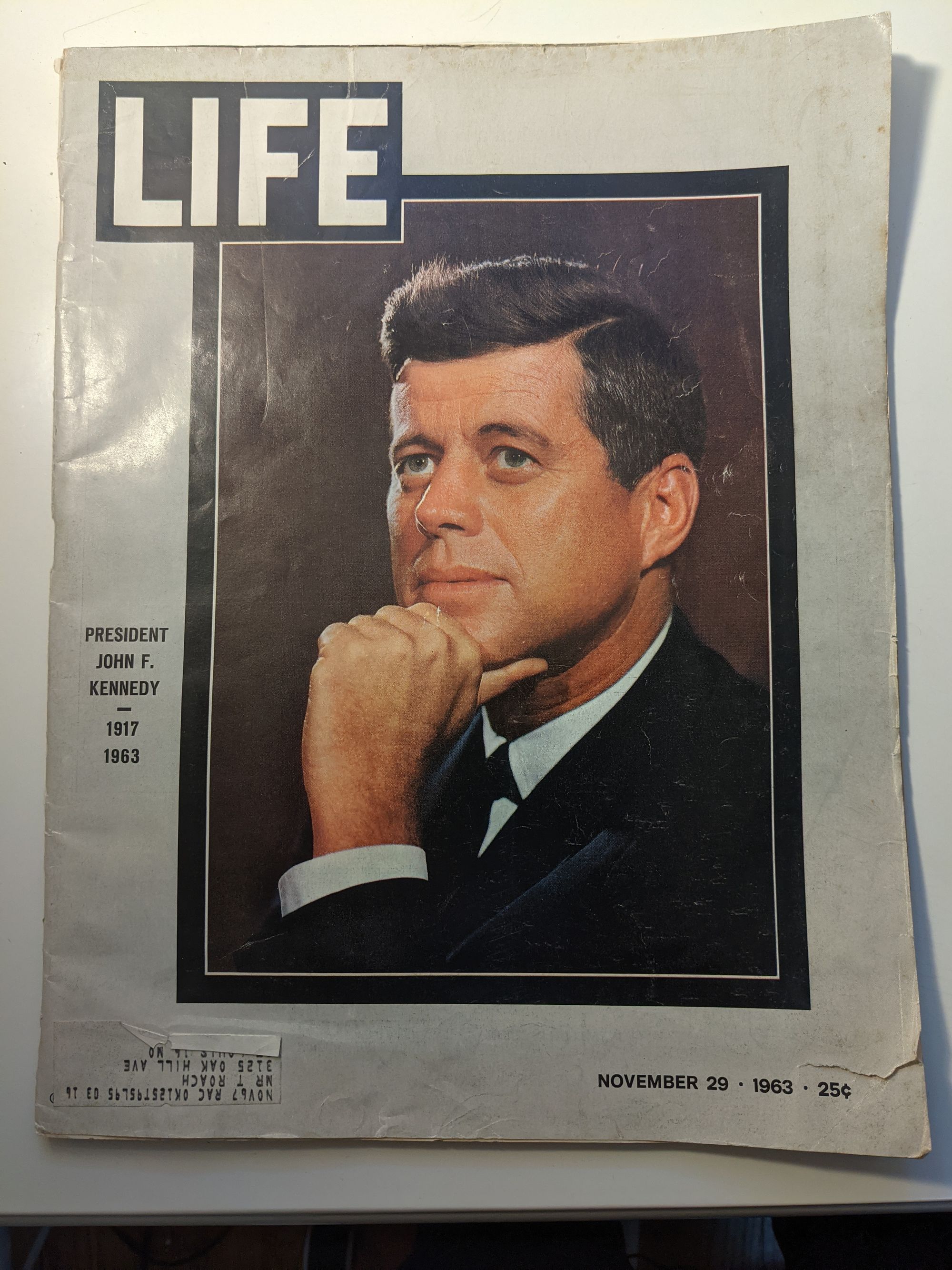

A recent find that might be of some interest here: I’m fond of old magazines, and there are a few vintage and thrift shops I go to here in Baltimore that reliably have piles and piles of them for sale. I was sifting through one the other day when I found this.

A LIFE Magazine from late November 1963. The cover story, obviously, is the Kennedy assassination. And as if to remind us in the present that major historical events are rarely quite as all-consuming as we imagine them to be, the rest of the issue includes advertisements for gin, cars, and cigarettes; articles on Tarzan and Anthony Newley; and a piece on the civil rights movement, evidently the second in a series on the “Negro in the North,” from one of the eminent political journalists of the day, Theodore White. As its subheading makes obvious – "The Angry U.S. Negro's Rallying Cries Are Confusing His Just And Urgent Cause" – the piece is about the language of the movement and the deployment of words and phrases that, in White’s view, risked making the civil rights struggle a magnet for intemperate radicals. “This militancy of language — supported by moral indignation, yet coupled with total confusion about what practical steps must first be taken,” he wrote, “has brought into the crusading Negro movement a fringe of extremist followers, white and black, moved by many other inspirations, both domestic and alien.” Again, this is November 1963. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which would ban public segregation and employment discrimination, was still many months away.

One divisive slogan White singled out was “Freedom Now”:

“Freedom Now!” is a mood phrase that links the militant leader to the passions of his followers. It is almost as difficult to quarrel with this phrase as to denounce The Star-Spangled Banner or George Washington; it is as impossible to reply to it as to the question, “Have you stopped beating your wife?”

But “Freedom now!” — no matter how wonderfully it lends itself to the emotional mood of orator and crowd, no matter how bravely the placards wave the phrase above good people softly singing We Shall Overcome — is a phrase with explosive potential. For the problems of bad housing and education, unemployment and lack of opportunity cannot be solved anywhere near fast enough to satisfy the cravings generated by orators who chant “We want it now! We want it all! We want it here! Freedom now!”

By wiping out reasonable public discussion of steps and procedures, the phrase “Freedom now!” blinds rather than clarifies. It could conceivably deliver leadership of the Negro community to demagogues who, if they insist that “now” is 1964, will force the major parties to polarize on this demand to the peril of both Negro and white.

The concepts “power structure” and “integration” were also problematic:

“Integration” can mean, for example, jobs. But in jobs, it can be a demand as solid as opening locked unions to fair opportunity for Negroes — or as silly as the unblinking complaint, on opening night, by pickets that Cleopatra, an African heroine, should have been played by a Negro rather than by a white woman — Elizabeth Taylor. “Integration” can also be applied to the symbolism of American life — it can support the insistence of Negroes that TV, movies, and stage begin to show the Negro in true achievement rather than as permanent servingman or it can invite the absurd proposal of some Los Angeles Negroes that they organize a protest march of 10,000 if no Negro girls are included among the beauty queen finalists for the Tournament of Roses parade on January 1, 1964.

[...] Enough survey work has been done to show that Negro parents, like white parents, are more interested tin the quality of education than in the chromatic proportions of the classroom. [...] Integration as applied to housing leads to hypocrisy. Outside of New York, there is no substantial evidence that any neighborhood of mixed colors, if left unprotected against the pressure, has ever been successfully and permanently stabilized against the torrent of in-migrating Negroes.

White also criticized established liberal and civil rights advocacy groups like the National Urban League for bending to the rhetorical demands of activists on the movement’s fringe:

“As voiced by the National Urban League in its demand for a national “Marshall Plan for Negroes,” the concept of equal opportunity must be expanded to include the “concept of indemnification”; and there is the warning that, if such sin-gold is not paid by white Americans to black Americans, the “power structure” is inviting “social chaos.”

The inflammatory language of the indemnification proposal illustrates a troublesome political paradox. The Urban League [...] is perhaps the wisest and most responsible of Negro civil rights groups; it knows best the internal problems of the Negro community in the city; it is most willing to accept Negro responsiblity for what must be done — and is consequently suspect among extremists within the Negro community as “a front for the white men.” The Urban League must, thus, advance, its share of extreme public demands — and, once these demands are voiced, all other groups, in order to be “militant” must back them too.

A failure to control the movement’s language, White finally warned, would have serious political consequences for liberals.

As Negro leaders continue to press the white liberal leaders of the North (Republican and Democratic alike) for the demands that rise from the inner torment of the Negro community, they also press white liberal leadership further and further away front he white working class — and the working class itself toward the temptation offered by anti-Negro demagoguery. By pressing hard enough the Negros can as thoroughly wreck or alter the nature of the present two-party system as did the Democratic radicals of the 1890s.

Of course, the civil rights movement did actually lead to a major political backlash and alteration of the party system that we’re essentially still living through. But that had less to do with the language activists deployed — most of which can’t really be seen now as unreasonable, especially circa 1964 — than with the substance of the radical shift in American life they managed to accomplish.

The criticisms being lobbed against identity politics now are about the same, but the political dynamics at work are, if anything, a bit worse than they were back then. A confluence of factors has convinced many that Democrats are much more indebted to radical language and ideas than they actually are; unlike the 60s, that political price hasn’t actually purchased much progress on policing, immigration, or any of the other live wire social issues we’re told Democrats are veering dramatically to the left on.

As I’ve written before, there’s no real solution to the fix the party’s in. Republicans are likely to sweep into power in Washington again and keep it for a very long time. But at some point in the next few decades, I think the American people are going to come to a point of decision on whether this country ought to be a democracy or not. Our task on the left is to convince them between now and then that we have to work and fight to make it one. There’s nothing else to be done. The Democratic Party isn't going to focus group its way towards overcoming the American constitutional order.

Reasons to Be Cheerful

We got the first unionized Starbucks on Thursday.

Reaction by Starbucks workers reaching a majority in the union vote at the Elmwood Avenue location. It becomes the first unionized shop for the corporation in the US. @WGRZ pic.twitter.com/zNcMdTUusr

— Steve Brown (@WGRZ_SteveBrown) December 9, 2021

Faith Bennett at Jacobin:

Despite only one out of three Buffalo Starbucks locations that held union votes walking away with official union recognition so far, Thursday’s elections signify an important moment in US labor history. Starbucks is designed to be union-resistant, and workers overrode the design. If they can do it, so can other Starbucks workers, as can café and food service workers nationwide.

Since announcing their intent to form a union in August, Starbucks Workers United have faced a brutal anti-union campaign from the corporation. The campaign has involved both common tactics like insistence on simultaneous votes, flyering, and captive audience meetings as well as more aggressive measures like crowding stores with managers and executives from across the country.

[...] Despite the fact that Starbucks employees at other locations are now well aware of the lengths that the company is willing to go to prevent them from joining a union, workers in Arizona have already publicly launched their own union efforts, and workers from several other stores throughout the United States have expressed interest in unionizing.

Bye.

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.