Popularism 2.0

Hey all. Let’s hop to it.

Recent Work

I was down with COVID for a bit, but I’m on the mend again and back to writing. Just ran a short column in The Guardian about gun politics:

The reality Democrats are loathe to admit is that if the NRA and the whole gun lobby sank into hell tomorrow, the chamber would still disproportionately empower voters in the most sparsely populated and conservative states in the country – the voters most likely to vehemently oppose not only regulations on gun ownership, but most of the major policies that Democrats, backed by majorities of the American public, hope to pass. And while significantly altering or eliminating the Senate obviously will not be in the cards anytime soon, Democrats are heading into this year’s midterms and the potential loss of at least one chamber of Congress without having taken more basic steps to balance the chamber, including the elimination of the filibuster or the admission of liberal Washington DC as a state.

Instead, they have left the American public chained to a fantasy – the idea that the surest and most defensible route to meaningful change is bipartisan action, no matter how intransigent the Republican party proves itself to be. That’s a delusion pushed not only by moderate politicians who have an interest in constraining the Democratic party’s capacity to pass left-of-center policies, but by the mainstream press, which mourns these shootings with calls for the parties to set aside their differences and “come together” on the issue.

But there will not be a grand coming-together on guns. The modest reforms on the table, even if passed, would do little to change the outcome of a culture war one side has already won. For all the ranting and raving we have heard from the right in the last few months about the cultural power liberals wield, the values of rural and exurban conservatives plainly govern the country here. It matters not a whit what liberals in cities like Buffalo or Pittsburgh think about living in a country where people are gunned down in stores and synagogues with legal assault weapons. An inescapable reality has been imposed upon them – there are more firearms than people in the United States.

Politics

As the piece suggests, I think the battle against gun violence in America broadly speaking has already been lost; as I’ve written previously, we’re entering a period where, like most of American history, sporadic outbreaks of mass violence will be normal. That said, federal gun control might help a bit at the margins, particularly when the mass shooters to-be are troubled young people legally purchasing AR-15s. It’s well known now that the most commonly discussed measures like background checks, red flag laws, and even a new assault weapons ban all poll very well. And that polling has become more and more central to arguments about the dysfunction of our federal political institutions over the last decade or so — as I and many others have argued, the fact that we can’t even get background checks past the Senate in the wake of these mass shootings is another bit of evidence that America isn’t really a functional democracy.

That’s become conventional wisdom among most liberals and leftists now, so we were about due for the contrarian take that’s emerged over the last week: the issue polls are misleading and gun control measures aren’t really very popular at all. Nate Cohn just ran this argument for the Times:

It’s one of the most puzzling questions for Democrats in American politics: Why is the political system so unresponsive to gun violence? Expanded background checks routinely receive more than 80 percent or 90 percent support in polling. Yet gun control legislation usually gets stymied in Washington and Republicans never seem to pay a political price for their opposition.

There have been countless explanations offered about why political reality seems so at odds with the polling, including the power of the gun lobby; the importance of single-issue voters; and the outsize influence of rural states in the Senate.

But there’s another possibility, one that might be the most sobering of all for gun control supporters: Their problem could also be the voters, not just politicians or special interests.

When voters in four Democratic-leaning states got the opportunity to enact expanded gun background checks into law, the overwhelming support suggested by national surveys was nowhere to be found. Instead, the initiative and referendum results in Maine, California, Washington and Nevada were nearly identical to those of the 2016 presidential election, all the way down to the result of individual counties.

As you can see here, the results in those four states were well below the 80+ percent support for background checks suggested by state-level projections based on national survey data.

Cohn and others have explored a few different explanations for that gap. Underperformance in referendums happens across just about every issue, suggesting there might be some poorly understood status quo biases at work at the ballot box. Moreover, the people who actually show up and vote obviously aren’t necessarily representative of the general population or the potential electorate. And polls might be capturing public opinion on issues before they’re actually batted around in the political arena or over the course of a campaign, which means they’re overestimates of what support will be when push comes to shove. But overall, Cohn suggests that the results here are indicative of a hidden apathy on guns that explains why we haven’t been able to pass new gun laws.

There are a few problems with this theory.

First, I don’t think it’s trivial that background checks won in three out of these four states— they only failed in Maine, which also happens to be one of the most rural states in the country. As I wrote on Twitter, the argument actually being made here is that gun control is dubiously popular because it won most of a set of four referendums — 6-8 years and several high-profile mass shootings ago — by less than the sixty-something point margin suggested by issue polling. This doesn’t sound like an especially compelling case to me.

Another problem with the theory that public opinion is preventing us from passing new gun control laws is that states have passed many new gun control laws. There was a wave of legislative activity after Parkland in particular — and even Republican legislatures passed some new restrictions. Some charts and an excerpt from the Times in 2018:

After the mass shooting in Parkland, Fla., in February, Congress did not act. But state legislatures did, passing 69 gun control measures this year — more than any other year since the Newtown, Conn., massacre in 2012, and more than three times the number passed in 2017.

[...] In the past, state laws were broken down roughly as you would expect, with stricter gun regulations in states controlled by Democrats and more permissive laws in states controlled by Republicans. That divide is still apparent, but the exceptions are increasing.

Democratic state legislatures passed more than twice as many gun restrictions as Republican legislatures this year, and Republican legislatures were the only ones to pass laws loosening restrictions.

Still, Republican chambers passed 18 gun control laws, and Nebraska — whose Legislature is conservative even though it is formally nonpartisan — passed another two. Republican governors also signed restrictions passed by Democratic legislatures in Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts and Vermont.

I don’t think the problem we’re facing at the federal level is especially complicated. It’s absolutely clear that most voters who nominally support gun control don’t actually prioritize it over other issues and concerns, especially when mass shootings aren’t fully saturating the news. For that and the other reasons already mentioned, the nearly unanimous support issue polls register for proposals like background checks are surely overestimates. That said, all available evidence taken together suggests to me that the American public leans toward support for the commonly discussed middle-of-the-road gun reforms. Additionally, the Democratic Party, which has only grown more solidly supportive of gun control over time, has won the popular vote in all but one of the last eight presidential elections. And as The Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein has noted, background checks won the support of 54 Senators — a bipartisan majority — representing nearly 80 million more Americans than their opponents when they came up for a vote after Sandy Hook in 2013.

They didn’t pass. And we’ve been unable to federally pass any of the measures that have succeeded at the state level since. Why? Because the U.S. Senate is a malign institution where the states least supportive of gun control wield a disproportionate amount of power relative to their size and where most legislation now has to meet a ⅗ supermajority threshold in order to pass — thanks, in part, to the intransigence of moderate to conservative Democrats who oppose eliminating or modifying the filibuster. That’s it! I understand that’s a boring diagnosis and I’m absolutely sick of writing it myself. But it’s the simple truth. Our federal system has made it very difficult to pass a federal gun control bill.

There’s a lot at stake in the arguments otherwise. Before Cohn wrote his piece, David Shor, who you’ll remember from our popularism debates, was pushing the public apathy thesis on Twitter.

We just delude ourselves about the politics here. This Maine background checks ballot measure is instructive - 40 point lead in polling, outspent the other side seven to one, still ended up losing. It’s pretty bleak. pic.twitter.com/EPGEezkXUI

— (((David Shor))) (@davidshor) May 25, 2022

If you believe the kinds of issue polls Shor generally points to in arguments about the Popular Things Democrats should be Doing, that data suggests the party’s right to be championing background checks and the other gun control measures now on the table. But as I wrote in my piece on Shor and co. for the New Republic in November, popularism has never really meant more than thinking strategically about policy in the ways that popularists happen to personally prefer, and there are all kinds of latent qualifications and exceptions buried within Do Popular Things as a guiding mantra — as originally expressed, there’s nothing really firm to grab onto there and the skepticism about the actual popularity of gun control underscores that. If we believe Shor that support for gun control measures are systematically overstated in issue polls — and it does seem true that they are, if not to the extent that Shor suggests — what does that tell us about the reliability and importance of issue polls to begin with? What should popularist policymakers do when the contextual information we need to make sense of them can be interpreted in different ways or when it’s unavailable? What if, for instance, there hadn’t been those referendums on background checks in 2014 and 2016? Would it have been right to go with the issue polls then? Or should we say that the public’s preferences are functionally unknowable from issue polls alone and bias ourselves towards the status quo?

It should be said that Shor offered what seems like an important update to popularism in the back and forth over this on Twitter: Democrats, he argues, should try to focus on issues where the public really trusts them, as measured, again, by opinion polls.

My main thing is that we should try to focus public debates on fights where the public trusts us (abortion is probably the best issue for us at the moment), and not ones where the public doesn’t. Especially if we’re running against a political party that openly wants to kill us.

— (((David Shor))) (@davidshor) May 25, 2022

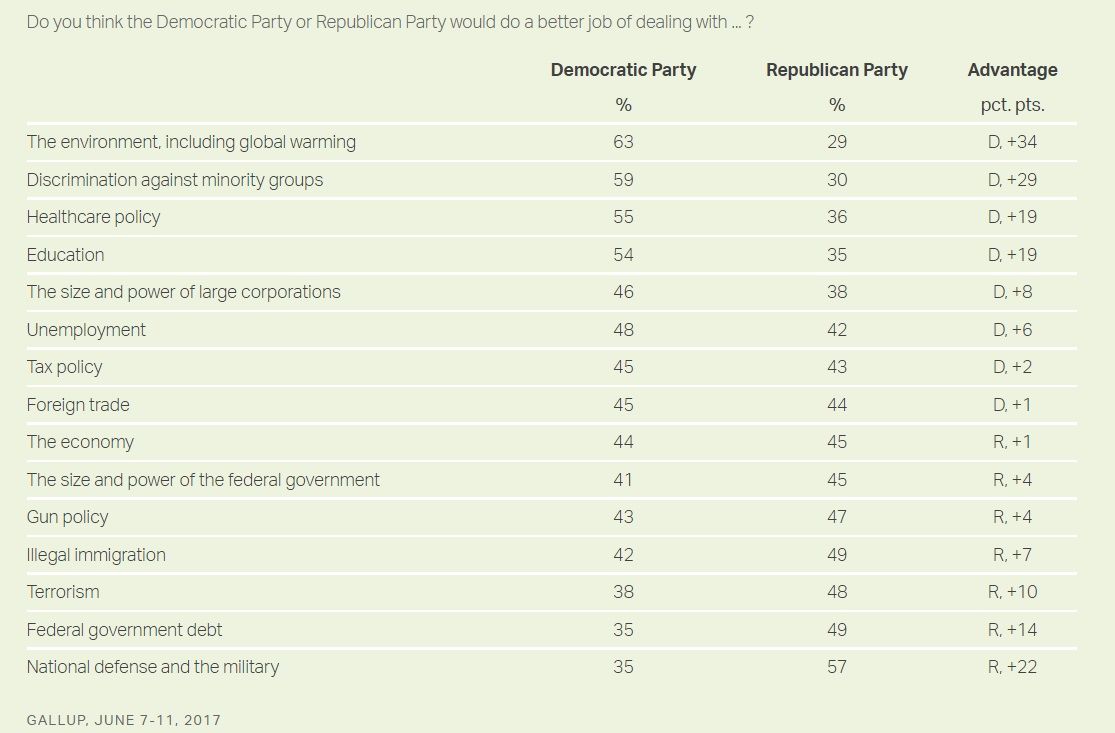

Based on Gallup’s figures from 2017, that would mean Democrats focusing on racial discrimination and climate change.

I’ve actually written previously for this newsletter about why the idea Democrats should talk more about discrimination is strange advice coming from this camp; in general I think there’s a problem with the assumption that political actors can really delimit the set of issues the public expects them to address. And whether you’re talking about race, climate, or any other issue, you still have to decide which actual policies to back and propose — so we return the problem of determining which of those policy stances are genuinely popular.

I’m glad that problem is being taken a bit more seriously in popularism and polling discourse now. While I think gun control is one of a few issues where the public’s broad preferences seem reasonably clear, public opinion is genuinely incredibly messy much of the time. Just take a glance at the state of abortion polling right now for proof. The challenges we face in ascertaining what people really want actually run a lot deeper than contradictory polls and election results, though you’ll have to wait for my book for me to go into them at length. All I’ll say now is that I’ve come to think it’s a mistake to believe democracy is about capturing the “will of the people” as a stable, coherent, and easily identifiable thing. What we should expect from democracy is the right to participate in a mostly authoritative collective decision-making process on equal terms — a process whose isolated outcomes may or may not reflect what “the people” as a whole want, if it can even be said that “the people” “want,” and know what they want, as one. And it’s clear that as far as gun policy is concerned, we’d be more likely to get something positive done on the federal level if the votes of all Americans actually counted just about equally.

Obviously, we can’t always expect the public to back what’s best. But I think believing in democracy means believing in the contestability of most issues. Even if it really were the case that the public didn’t support basic gun control measures, I don’t think that would make it fundamentally wrong for policymakers to support or pass them — ideally they’d face the public and try to win people over. This is one of the classic questions small-d democrats have always had to think through and confront. But I’d rather we lived in a country where we had to confront it directly, rather than in a quasi-democratic republic where the challenges of real democracy aren’t even accessible to us yet.

One other thing: what the public apathy thesis and the talking points the right is converging towards on guns have in common is the premise that the American people are the real problem; the right in particular seems to be talking itself into the idea that Americans have been possessed by evil. And in general, I feel like the center and the right have been casting more and more aspersions on the wisdom and morality of the masses in recent years. This seems like an opportunity for the left — to be the last ones standing loudly and proudly behind the idea that the American people are imperfect but fundamentally good and deserving of more power, at the ballot box and at work, than the center and the right think they should have.

Reasons to Be Cheerful

Blue states are already moving to pass more gun control. From Vox:

While Senate Democrats attempt to reach a long-shot compromise on gun legislation, blue states are taking their own steps to respond to the recent mass shootings in Buffalo, New York, Uvalde, Texas, and Tulsa, Oklahoma.

New York became the first to pass a slate of new gun control bills before the end of its legislative session on Thursday. California, New Jersey, and Delaware also have legislation in the pipeline.

These states, where Democrats have trifecta control of government, already have some of the strictest gun control laws in the country. Soon, they’ll likely have even stronger laws, which should mean less gun violence: States with tougher gun laws have lower rates of gun-related homicides and suicides, according to a January study by the gun control advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety.

A Song

“Chaos Space Marine” — Black Country, New Road (2022)

Bye.

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.