Giving Thanks for Survey Research

Hey all,

I wanted to take a post to talk about a few recent polling reports I’ve been thinking about recently. Let’s hop to it.

Politics

Earlier this month, Jacobin and YouGov released a report on progressive messaging and working class voters called “Commonsense Solidarity: How a Working-Class Coalition Can Be Built, and Maintained.” Its findings were based on a survey of non-Republican and non-college educated voters in five states — Nevada, Michigan, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Wisconsin — who were asked to make choices between hypothetical candidates with certain characteristics and running on different versions of Democratic messaging.

None of their findings were particularly surprising to me, but several key ones did contradict a few prominent lines of thought on the left. For starters, the survey amounts to a strategic repudiation of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 and 2020 campaigns, which hoped that a new left constituency could be mobilized by the substance of a more progressive agenda than the Democratic Party had been willing to offer. As I’ve written before, that wasn’t borne out by the actual results of the primary, and it isn’t reflected in Jacobin’s data either. “Our experimental results provide little evidence to support Sanders’s theory,” the report’s authors wrote. “The evidence suggests that it is unlikely that low-propensity voters fail to vote because they don’t see their progressive views reflected in the political platforms of mainstream Democratic candidates.” The report also rejects the idea that distance from the Democratic Party helps progressives win over working-class voters. “Indeed,” they wrote, “independent candidates were viewed slightly less favorably than Democrats among survey respondents, though this difference was not statistically significant. Further, we observe no meaningful differences in support for independent versus Democratic candidates across differences in geography, income, race, and class.”

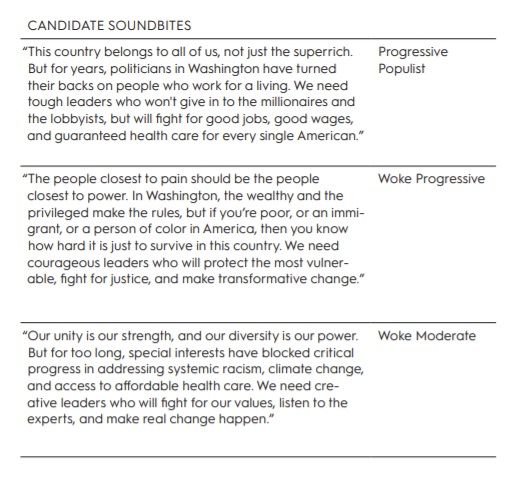

Anyone who’s followed the last five years of progressive political debate should understand that these aren’t trivial concessions for Sanders backers to make, and Jacobin deserves a tremendous amount of credit for seeking out and presenting challenging new data here. The report’s other main conclusions, though, align more neatly with the identity-skeptical and class-centric approach they support. While the report found that the substance of racial justice efforts doesn’t actually alienate working class voters, the identity-forward “woke” messaging shown above was less appealing to working class voters than the more identity neutral “populist” anti-elite messaging people associate the Sanders campaigns with. This was effectively the report’s headline result. “Centering economics and downplaying woke messaging is particularly important for progressives competing outside of liberal enclaves, where rural/small-town working-class white voters and white voters with low educational attainment wield disproportionate electoral influence.”

There are a couple of things to say about this. First, this is essentially Shorism. And as I’ve written about Shor, the problem progressives and Democrats more broadly are facing is less that progressive candidates in rural Kansas have been running on defunding the police than that certain factors, including a nationalized political media environment, have combined to undermine the rhetorical strategies Democratic candidates use to appeal to the moderate and conservative parts of the electorate. And those factors aren’t easily captured in polling like this — respondents are going to react differently to faceless, nameless hypothetical candidates in a survey than they will to actual candidates given the pressures and counter-messaging at work in real-world politics.

The second thing to say is that the differences between the types of Democratic messaging tested don’t actually seem as large as the authors’ write up of their results implies — the progressive populist messaging polled best, but working class respondents responded positively to all the left-of-center approaches. Additionally, race obviously matters here — the working class is obviously much larger than the white working class, but it’s white working class voters who matter the most in federal politics. And another question that’s been looming over Democratic politics is whether identity forward messaging specifically motivates black and Latino voters more than other kinds of rhetoric. The report’s findings on these questions are kind of hand-waved away in a single paragraph:

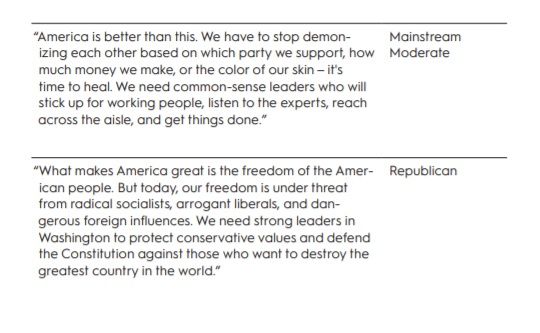

Populist rhetoric did not produce very large differences among racial or ethnic groups. White respondents narrowly preferred the progressive populist soundbite over the mainstream moderate, with the woke soundbites considerably behind; black respondents narrowly preferred the progressive populist messaging over the woke progressive and the woke moderate soundbites; and Latino respondents preferred the mainstream moderate rhetoric, with the progressive populist soundbite coming in second.

Each piece of this is important, though, and the actual graph here is worth a look.

The error bars here suggest there wasn't actually a statistically signficant difference between white working class support for progressive populist messaging and their support for mainstream and woke moderate messaging. Whether that’s a good or bad result for the left is a glass half full/half empty kind of question, I suppose — Sanders style messaging seems to neither help nor hurt. The graph also suggests that populist progressive messaging and woke progressive messaging were functionally tied among black working class respondents. Latino respondents seemed partial to moderate rhetoric, although, again, the differences do not seem statistically significant. Put together, we see that white working class voters aren’t too into identity-focused rhetoric and are ambivalent about Sanders style messaging while black and Latino voters aren’t as motivated by identity-focused rhetoric as some casually assume, although it doesn’t seem to hurt terribly with these constituencies either. Again, these are results prefigured by previous polling and the results of the last Democratic primary. But this survey took a novel route to those conclusions, and there’s a lot of material here on other interesting questions, including whether candidate demographics really matter to working class voters — the report optimistically suggests they don’t, at least in the vacuum of a poll — and how pollsters and analysts should go about identifying class positions in the first place.

On the other side of the center-left discourse spectrum, The Atlantic recently ran a survey of its own on the culture wars. The magazine’s Olga Khazan:

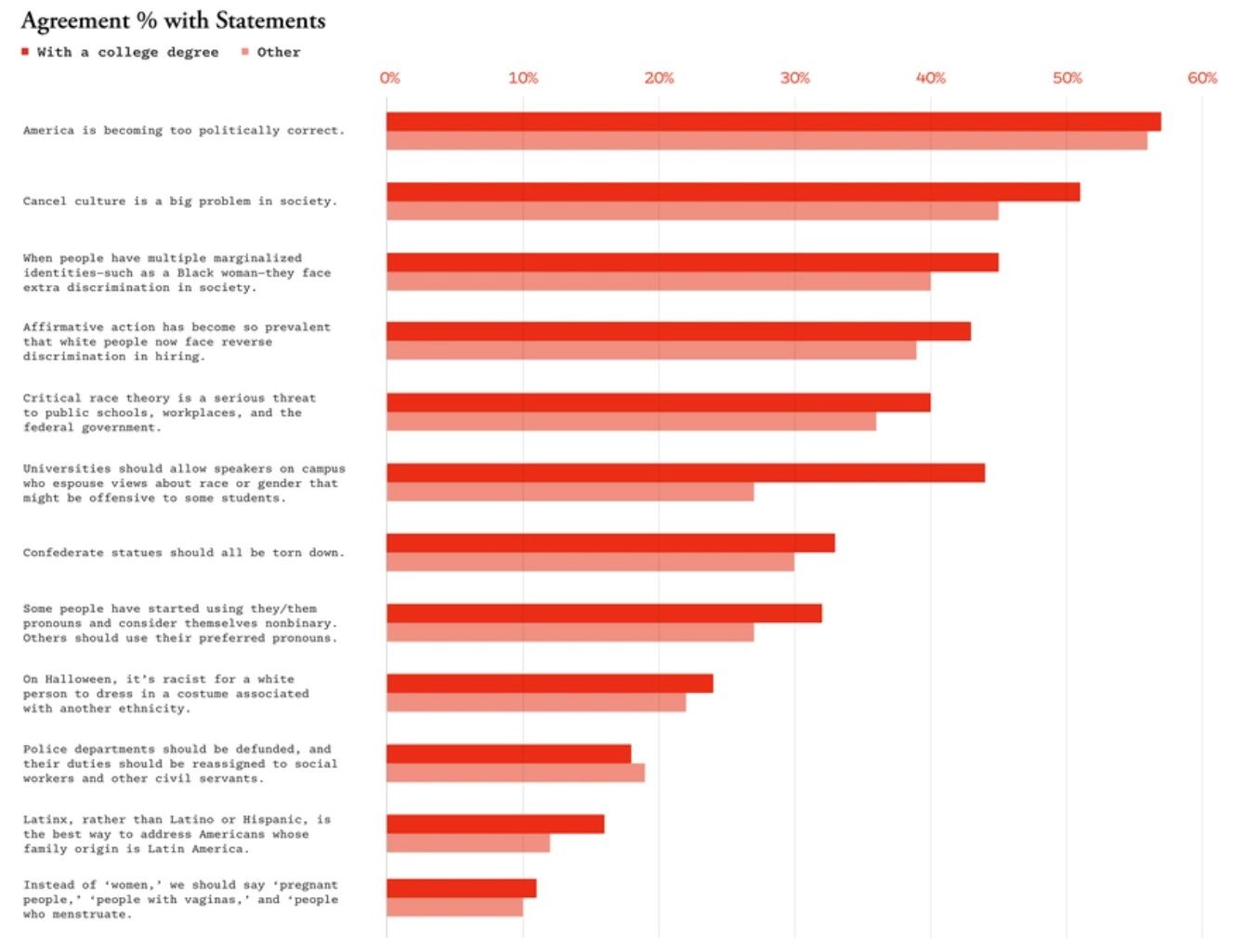

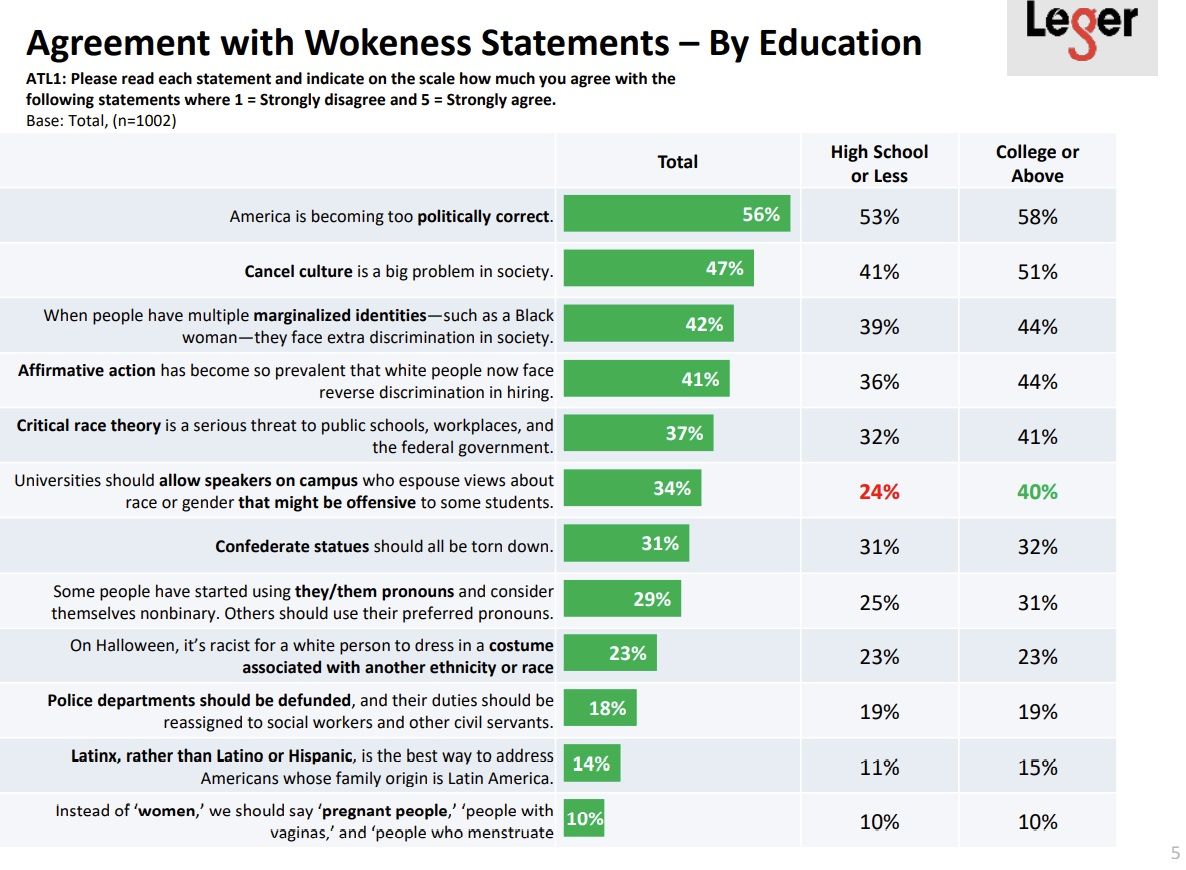

For the poll, Leger surveyed a representative sample of 1,002 American adults from October 22 to October 24. We asked for respondents’ agreements with various statements, shown in the chart below, that are often invoked by conservatives and moderates as being associated with people who are “woke.” The results showed that there was no significant difference between people with college degrees and those without them on the question of whether America is becoming too politically correct (slight majorities of both groups agreed somewhat or strongly). The same was true for believing “cancel culture is a big problem in society”—51 percent of degree holders agreed, as did 45 percent of those without degrees.

There was also no difference on questions pertaining to support for defunding the police; a preference for saying “pregnant people” instead of “pregnant women” or “Latinx” rather than “Latino or Hispanic”; for using gender-neutral “they/them” pronouns upon a person’s request; or agreeing that it’s racist to wear a Halloween costume associated with a different race or ethnicity. Less than 30 percent of respondents agreed with any of those, and it didn’t matter whether they had a college degree or not—at most, the college-educated were more likely to endorse these views by a few percentage points.

This is another place where looking at the actual charts and figures is instructive.

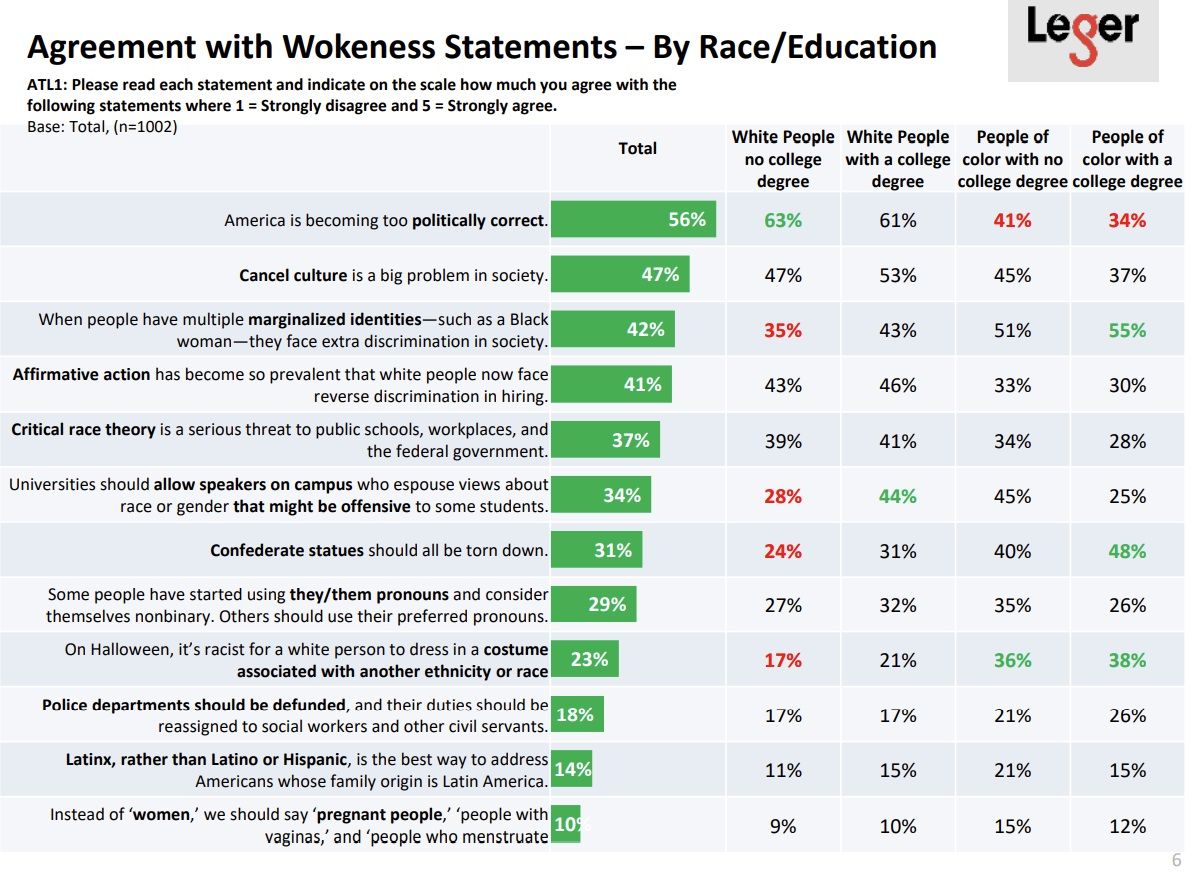

I think Khazan actually understates the differences here – it’s notable that those without college degrees were less likely to support the anti-woke positions on political correctness, affirmative action, cancel culture, critical race theory, and campus speech. This pattern held mostly true even among whites specifically — white respondents without college degrees were significantly less likely than whites with them to support the anti-woke positions on cancel culture and campus speech and slightly less likely to support the anti-woke positions on affirmative action and critical race theory.

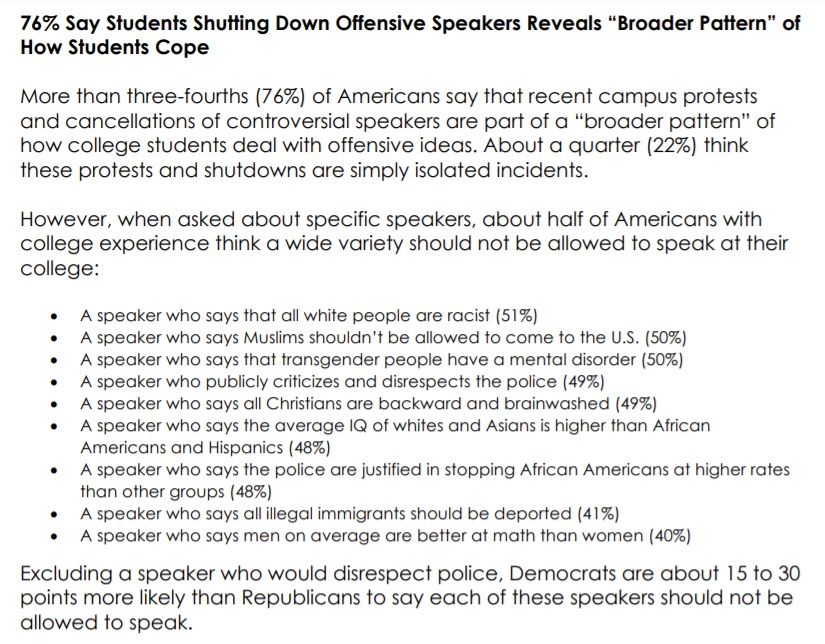

The difference on campus speech is particularly stark — enough so that it’s actually plausible to me that the phrasing of the question might have confused some respondents. Only 28 percent of working class whites said universities should invite speakers with offensive views on race or gender issues. 44 percent of whites with college degrees — notably, still a minority — said the same. While I’m not sure the actual difference is quite that stark, the result does line up with other polling I’ve seen over the years that suggests the general public isn’t nearly as gung-ho about free speech on campus as op-ed columnists would have us believe. Take this Cato survey from 2017 for instance.

Anyway, The Atlantic's numbers for nonwhites are interesting too. People of color without college degrees were more likely than minority graduates to say political correctness, cancel culture, and critical race theory are problems, more critical of affirmative action, more supportive of campus speakers with offensive views, and less likely to support tearing down confederate monuments. But, amusingly, people of color without college degrees were also substantially more supportive than graduates … of using trans pronouns and the term “Latinx.”

Again, both are still minority positions and this survey is just one of many on these questions. But the figures here are undeniably funny at the very least. I think the main substantive takeaway, though, is that caring about "wokeness" is itself a class and education signifier – the working class people pundits assume are being alienated by the left's cultural positions aren't actually as plugged into these conversations in the first place as the college educated. And to the extent that they are, their positions on the relevant questions are messier than one might expect reading The Discourse.

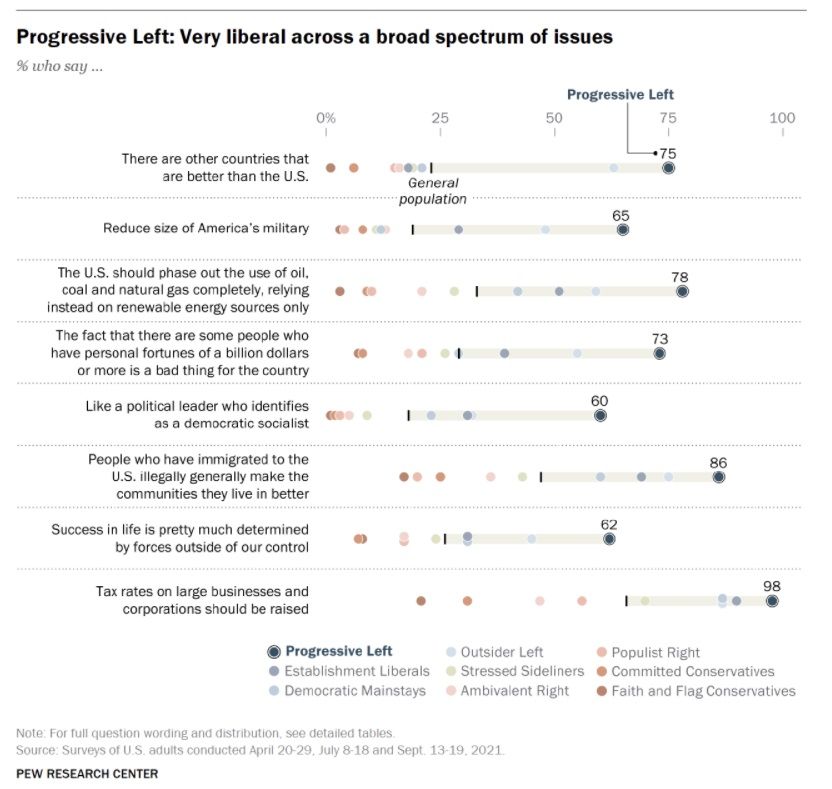

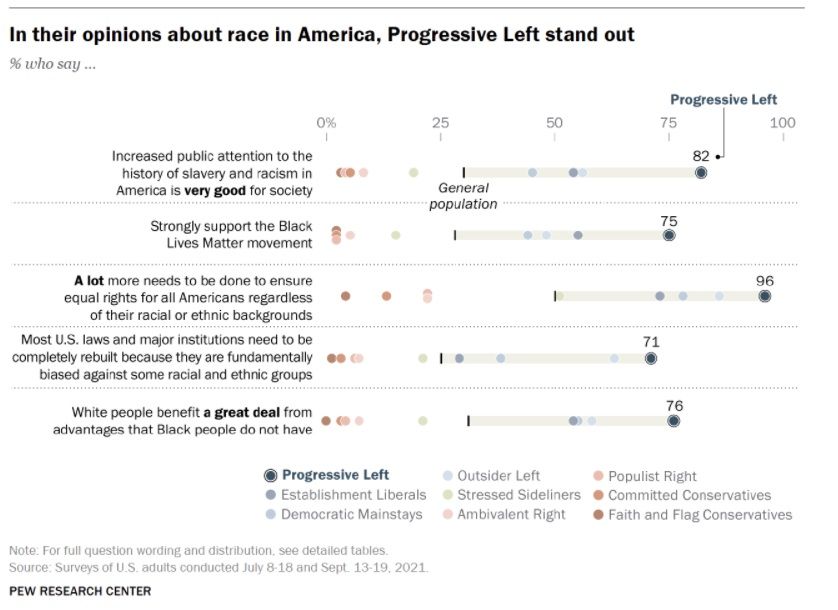

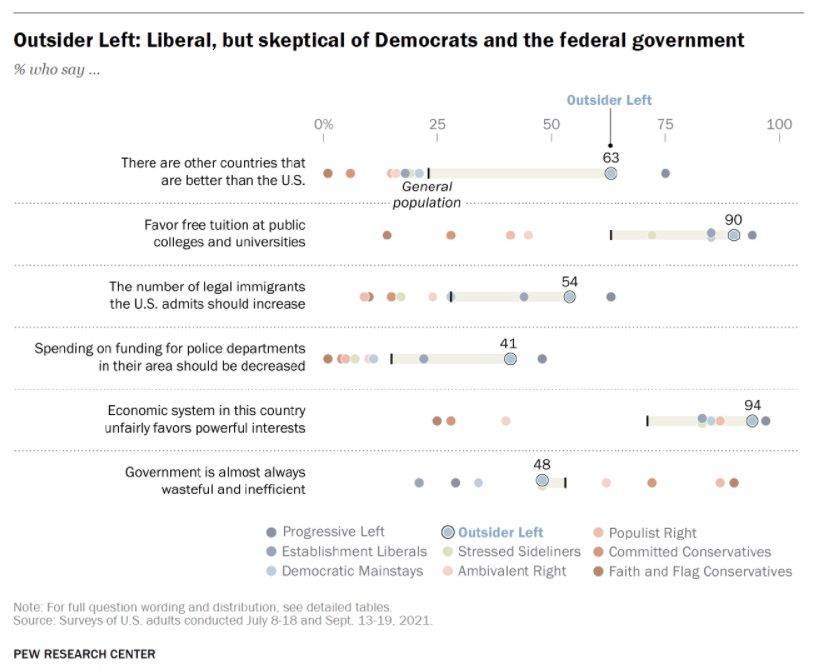

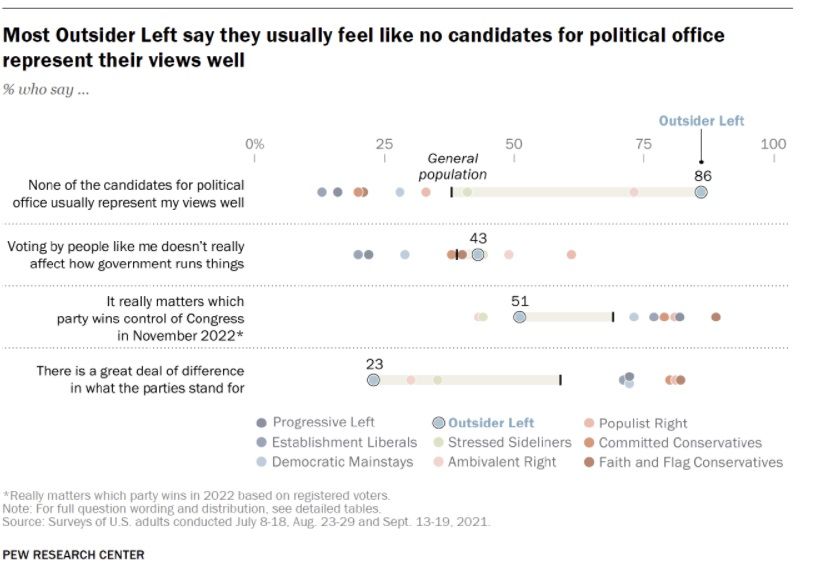

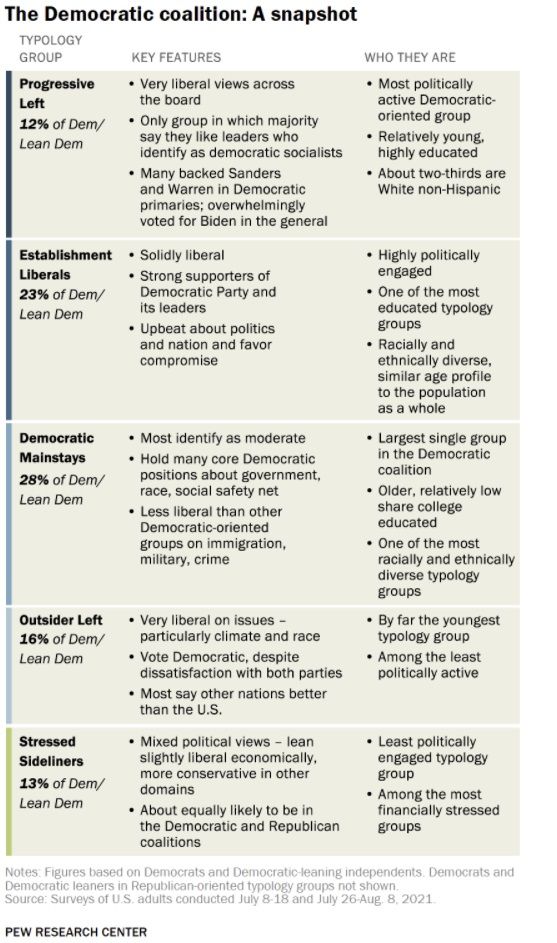

Lastly, Pew recently published its eighth typology of the American political landscape. I generally find Pew’s work extremely useful and illuminating on a variety of questions and this report is no different. There’s a lot of material on the composition of both the Republican and Democratic coalitions, but I want to focus here on two constituencies Pew identifies on the Democratic side of things — the Progressive Left and the Outsider Left. These groups are roughly what they sound like — the 12 percent of Democrats on the Progressive Left are conventional progressives with consistently left-leaning positions on just about every policy issue, while the 16 percent of Democrats on the Outsider Left are very young, mostly progressive voters who are a good bit more skeptical about government and a lot more critical of the Democratic Party and our political system overall.

I think I lean towards the Outsider Left. The group as a whole is more skeptical of government, yes — there’s an even split between those who think government is mostly wasteful and those who think it’s better than it gets credit for — but a most seem to have faith in government’s potential. 73 percent say they would support a bigger government with more services while 23 percent would prefer a smaller government with fewer services.

Combined, the Progressive and Outsider Left comprise 28 percent of the Democratic voters and leaners. That’s a minority too small to set or influence the party’s agenda more than the limited extent it already has. But it’s also a minority too large to be safely dismissed and ignored — which isn’t to say that the Party won’t unsafely dismiss and ignore it. If we combine the two with the 13 percent of deeply ambivalent conservative-ish Democrats who are “Stressed Sideliners” in Pew’s typology, we find that roughly 41 percent of the Democratic coalition has reason — whether they act upon it or not — to be disgruntled with their position in Democratic politics, albeit for ideologically divergent reasons.

This might concern me if I were a Democratic strategist. For all the thought we on the left give to how we might bring normal voters to our side, it shouldn’t be forgotten that the survival of the current alignment of power within the Democratic Party will depend upon establishment figures winning over more left wing voters as middle-of-the-road Democrats age. That’s not an enviable task; I really don’t know how they’d go about deepening the attachment of young voters to the party without making policy and rhetorical concessions they don’t want to make. I guess the hope is that progressives are going to mellow out as they age. Doesn’t seem like it’s happening yet – during the 2020 primary, Sanders' coalition included "young voters" approaching their 40s – but we’ll see.

The other headline number for me here: together the Progressive and Outsider Left comprise 16 percent of the overall adult population. That adds up to roughly 41 million people. That’s a large number in absolute terms and certainly a much larger constituency than all the chiding about social media, activism, and “real life” suggests. But it’s still not nearly enough.

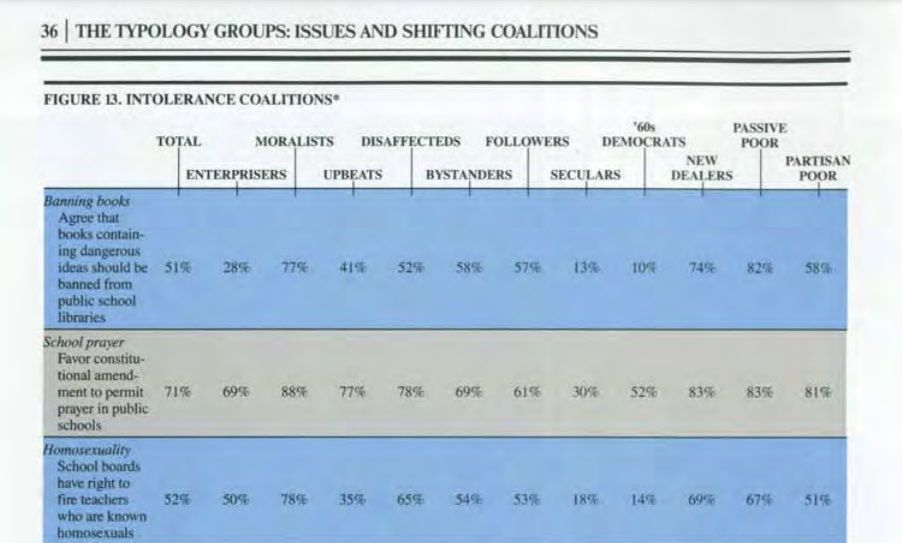

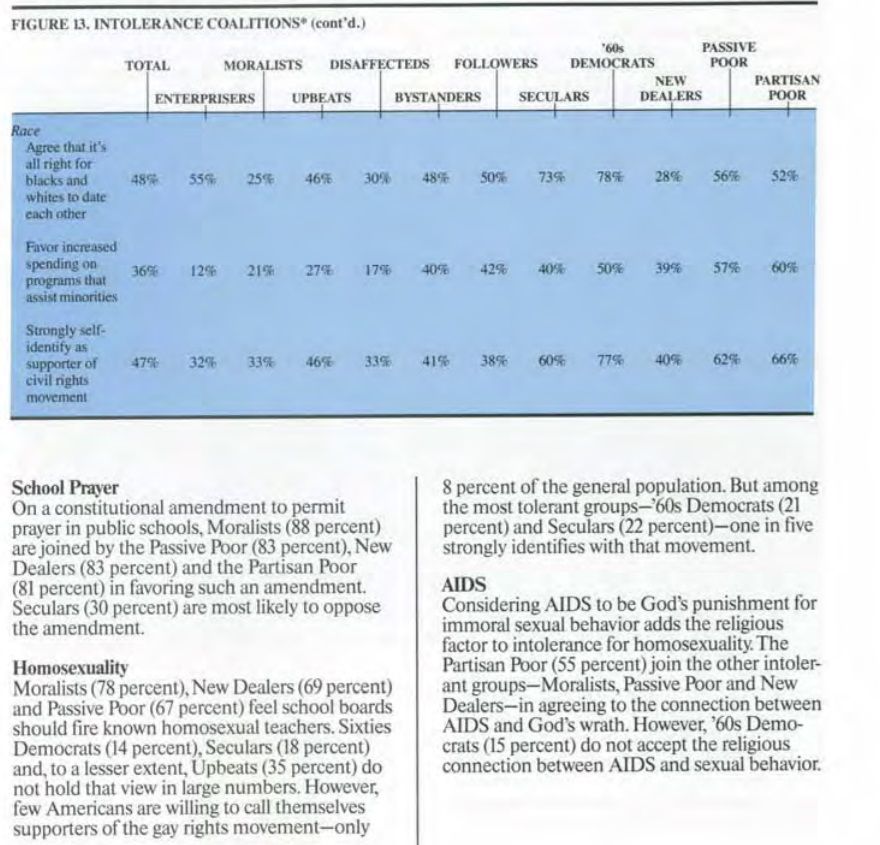

As a final note, Pew's first political typology from 1987 is a good read, particularly for those still invested in the popularism debate. I don't think the popularists reckon very seriously with what their recommendations for the Democratic Party would have been back then, but we don't really have to guess. The numbers are clear.

Taking a break for the holiday this week. Have a Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.