Fellas, Is It Anti-Democratic To Defend Democracy?

Hey all. Let’s hop to it.

Politics

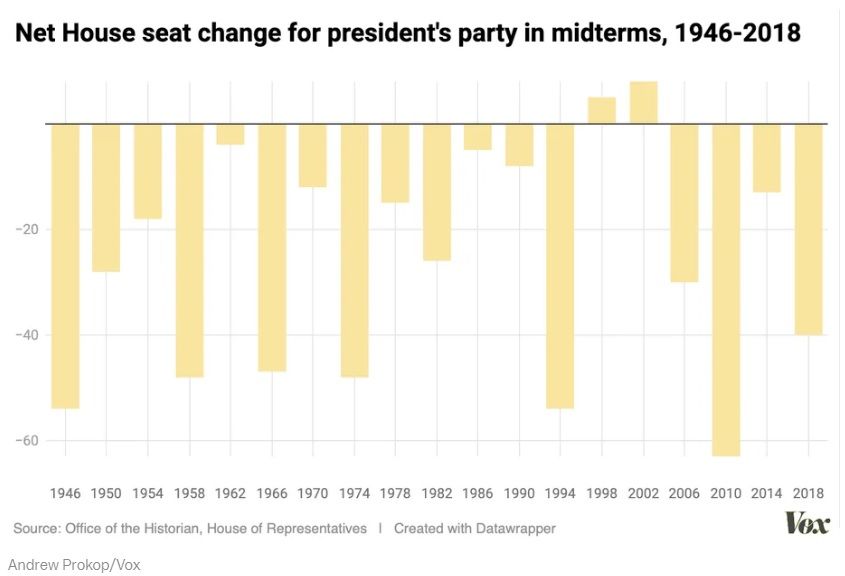

As you might have heard, there’s an election tomorrow. I was going to write about it today, but I don’t see the point, really. We’ll have concrete results to talk about tomorrow and in the days and weeks ahead. If you absolutely must know what I’m thinking at present, I’ll refer you again to the chart below:

Now, over the last week or so on Twitter, there have been a few running debates— maybe some of the last we’ll have on the site as we know it — about the Democrats’ democratic rhetoric. Some have argued, strangely, that Democrats haven’t really talked about democracy much in the run up to the election. Others have argued, just as strangely but more interestingly, that the speeches Democrats obviously are making about democracy and right-wing threats to it are actually anti-democratic. Here’s Shadi Hamid for instance:

I feel like I’m succumbing to a level of frustration that I’m having a bit more trouble keeping inside. There are some things I really do care about. They primarily have to do with the democratic idea [...] And Democrats increasingly seem to be embracing anti-democratic rhetoric in the name of saving democracy from those who might end it. In his recent “pro-democracy” address, President Biden—and I exaggerate only slightly—basically made a version of the following argument: ‘Democracy is dying, therefore to save democracy you must vote for my party. If you vote for the other party, you are helping democracy die. Democracy is on the ballot, and there is only one choice.’

Again, the argument here, as I understand it, is that a party that respects democracy cannot, normatively speaking, tell voters that they’re the only truly democratic choice available on the ballot.

Now, let’s consider this for a second. Imagine a liberal democratic party facing an out and out Nazi Party or a totalitarian communist party in an election. In their pamphlets and literature, they point out to voters that their opponents have promised to send dissenters to a concentration camp or the gulag; they gingerly suggest this policy would be suboptimal from a democratic perspective. This would be democratically wrong, clearly, given the norm Hamid is defending. Challenge the Nazis and Stalinists on other policy grounds and avail yourselves of other reasons to oppose the jackboots rounding people up and taking them away. But do not, under any circumstances, suggest that the totalitarians are totalitarians in the course of winning voters over; raising democracy’s defense as an issue would itself be a deplorable betrayal of democracy.

That doesn’t wash, obviously; even if it made sense to consider arguing against the Nazis on democratic grounds anti-democratic, democracy would plainly be better off if the liberals did it anyway. All told, this is a terrific example of a rhetorical pattern I’ve noticed in our free speech debates and elsewhere — over and over again, we see people articulate sweeping and untenable principles that collapse under a moment’s scrutiny (“people shouldn’t be fired for their speech,” or “arguing that an opponent threatens democracy is undemocratic”) rather than articulating and defending substantive positions on the specific matters at hand (“I do not think x should have been fired for saying y,” or “I am substantively unconvinced by the arguments Democrats are making about Republicans and democracy”).

In a recent Substack, Josh Barro makes an argument that seems slightly different:

When Democrats talk about “democracy,” they’re talking about the importance of institutions that ensure the voters get a say among multiple choices and the one they most prefer gets to rule. But they are also saying voters do not get to do that in this election. The message is that there is only one party contesting this election that is committed to democracy — the Democrats — and therefore only one real choice available. If voters reject Democrats’ agenda or their record on issues including inflation, crime, and immigration (or abortion, for that matter), they have no recourse at the ballot box — they simply must vote for Democrats anyway, at least until such time as the Republican Party is run by the likes of Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger.

This amounts to telling voters that they have already lost their democracy.

As I’ve written previously, I think the party’s messaging on democracy can be improved. I’d also take the professed concerns of Democratic leaders a touch more seriously if the party hadn’t spent the year, as Barro rightly notes, trying to help far-right candidates spewing nonsense about the 2020 election win Republican primaries. But the argument being advanced in the above is specifically about the internal logic of the Democrats’ case. Democracy for the Democrats, in his words, is “about the importance of institutions that ensure the voters get a say among multiple choices and the one they most prefer gets to rule.” You can pick that statement apart in about fifty different ways, but let’s take it at face value and assume that’s what Democrats believe. They nullify that principle, the argument goes, when they say only they are committed to democracy; to do so is to imply that voters already lack an actual “say among multiple choices.” But this is nonsensical. Making an argument that there’s only one correct choice among options obviously doesn’t bar people from making an alternative choice or suggest there isn’t a valuable choice to be made. In fact, the act of making an argument to voters in the first place suggests a valuable choice is available to them. And Barro goes on to predict that the electorate will, because that choice is real and valuable, democratically reject the Democrats’ pitch. So what’s the problem? What we have here, really, is an argument that fuzzily places the shape and health of democracy outside the realm of sensible democratic contestation; it is itself anti-democratic in that sense.

That’s the response to Barro as an abstraction; as a practical matter, I can’t say I care all that much what arguments Josh Barro deems democratically permissible for reasons John Ganz has already articulated:

Look, they even say it all the time—“We’re a republic, not a democracy,”—or some such similar bullshit. It’s just the simple truth: They don’t want the country to be a democracy anymore. They know it. We know it. But for some reason all these pundits say we shouldn’t say it. The centrist pundit, in either his cynical or naive form, loves to warn about the dangers of rhetoric, but this kind of equivocation about the parties sets the predicate for political cynicism and resignation: everyone shrugging their shoulders and saying, “Well, they are both bad, they Democrats have their authoritarian side, too, after all. I mean, look at all that manipulative ‘ saving democracy’ talk.” It also allows us to settle for the curtailing of democracy, but not an absolute destruction: some kind of hybrid regime: “Well, it’s not really an authoritarian dictatorship, there’s an opposition, after all, look, there’s still a Democratic mayor of…Ann Arbor.”

My one spot of difference with Ganz is in the “anymore” above; as I’ve written before, I do not think the United States is a meaningfully democratic society. That said, whether you believe that America has never been a democracy or that American democracy is on its way out, the immediate task ahead is clear. The future of democracy in this country rests on our stopping the right; we’ll only do so if we speak clearly and convincingly to the American people about what they’re doing, what they’re after, and why democracy is worth fighting for.

A Song

“Bad Advice” — Protomartyr (2014)

Bye.

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.